Heralded as a pioneer today, Lucile Berkeley Buchanan enrolled at what is now the University of Northern Colorado in 1903, amid little fanfare.

As Polly Bugros McLean documents in her biography of UNC's first African American graduate, Buchanan left Denver for Greeley days before fall classes started.

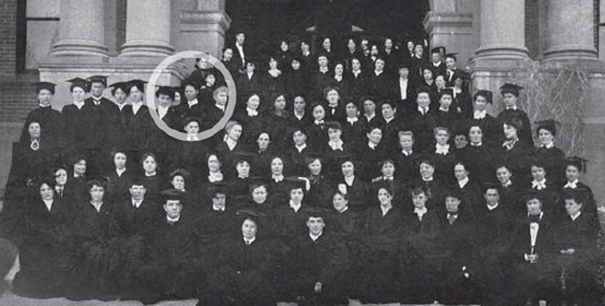

Top image: Lucile Buchanan, pictured here in her 1905 class photo, was the only African American student in her 1905 graduating class, which consisted of 115 females and 14 males.

With only one building on campus then, Buchanan took the typical approach of students at the time. She secured off-campus housing, renting a room from the family of the chief of the fire department, abolitionists who welcomed Buchanan into their home.

In many ways, she was following in the footsteps of her older sister. Laura had relocated to Greeley in 1899 to attend the Normal School with hopes of becoming a schoolteacher before her life was tragically cut short.

The pain of her sister's suicide weighed heavily on her and her family, McLean notes. A determined Buchanan, with the same career aspirations, finished her degree requirement in two years — taking 96 credits to earn her teaching credential. In 1918, she would go on to become the first African American woman to graduate from the University of Colorado, with McLean’s research serving to set the record straight.

Above:Buchanan’s graduation photo from the Normal School (now UNC), 1905 (image courtesy Polly Burgos McLean).

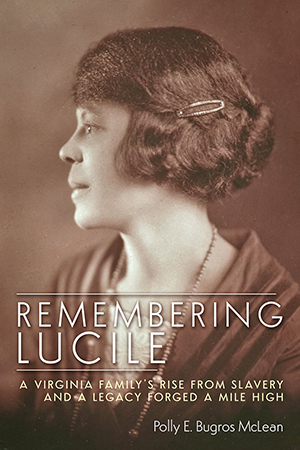

McLean chronicles Buchanan's rich story in "Remembering Lucile: A Virginia Family’s Rise from Slavery and A Legacy Forged A Mile High." After learning of Buchanan from a newspaper article published in 1993, McLean crisscrossed the country to find sources. Her travels took her to the plantation in Virginia, where Buchanan's parents were enslaved before emancipation; Buchanan's former residence in the Kansas City area; the former home of Buchanan's sisters in Los Angeles; and a windswept town on the Texas prairie to track down the man who purchased Buchanan's Denver home after her death at age 105 in 1989 — the same man who also had acquired many of Buchanan's heirlooms as part of the purchase.

When McLean discovered in Buchanan’s CU transcript that she had graduated from UNC, McLean also visited campus and worked with UNC's Archival Services to locate Buchanan's 1905 graduation photo in the yearbook (pictured). In the process, she proved that Buchanan was indeed UNC's first African-American graduate. In spring 2019, McLean returned to UNC and discussed the book during a campus presentation.

Many parts of McLean's book document the adversity and discrimination Buchanan and her family faced. An example: In return for earning teaching degrees, Normal School graduates were required by the state to teach in public schools. Colorado districts, reluctant to hire a black educator at the time, turned her down for multiple teaching positions upon college graduation in spite of her sparking credentials and academic record.

“She even applied to a school in Maitland, Colorado, a coal-miner’s town about 165 miles away from Denver,” McLean said.

After being passed over there, Buchanan landed her first job thanks to her minister

who connected her with Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock, Arkansas, to officially

start what would become a successful 44-year career in education.

“She never wanted to leave Colorado but was forced to,” McLean said.

During her campus presentation, McLean said Buchanan never sought the spotlight or

the slightest recognition for her accomplishments in spite of her compelling story.

"I do believe what we have missed as historians and archivists and everybody that

is interested in preserving that history is that we often define history for those

who made the nightly news, those who have done something substantial or those who

have done something wicked; they get the attention, the celebrities," McLean said.

“I come from the perspective that talks about history from below, and it’s that history

that we don’t pay much attention to and is the history that really makes the nation.”

— Written by Nate Haas, UNC News and Public Relations

An excerpt from McLean's book (republished with permission from the author):

An excerpt from McLean's book (republished with permission from the author):

Several days before the start of the semester, nineteen-year-old Lucile packed up her college accoutrements and loaded them into the back of her father’s wagon for the ride to the Union Depot in Denver. She boarded the one-car passenger Union Pacific and Colorado and Southern Railway train and headed to the one-story stone railroad depot in Greeley, fifty-four miles away, where classes would begin on Tuesday, September 8, 1903.

At this time, the school consisted of one building, Cranford Hall, which served both administrative and academic purposes. Without housing or boarding facilities on campus, students had to room and board with private families, who charged from $3.50 to $4.50 per week. Lucile found housing at 1115 Ninth Avenue with Edward Moore Nusbaum, a local brick contractor from Ohio; his Canadian-born wife, Agnes Strickland; and their sixteen-year-old son, Jesse. Back in 1886, when Edward served as the chief of the Greeley Fire Department, he donated $25 ($692 in 2017) to the building of UNC. The Nusbaums, staunch Republicans and abolitionists, were part of the settler class that arrived in Greeley during the post–Civil War era.

While economic factors might have played into their decision to host Lucile, the strength of their moral conviction as abolitionists may have also contributed to their decision to bring a Black woman into their household.

Lucile had worked diligently in high school and took great pride in her acceptance into UNC. Her transcript demonstrates that she applied the same academic rigor to the eighteen-week Normal School semester, which required her to attend twenty-five recitations per week. A year of schooling added up to a total of fifty term hours or 900 recitations. During her two years (four semesters) at Greeley, she took all the required courses—arithmetic, English, psychology, physical education, pedagogy, music, geography, reading, manual training, and practice in teaching—for a total of ninety-six credits. Her only elective, taken in her senior year, was German.

She was the only Black student in her 1905 graduating class, which consisted of 115 females and 14 males. To celebrate her success in Greeley, the Statesman reported on Saturday, June 10, in its City News section, “Mrs. S. L. Buchanan and a few of her friends left for Greeley this week to attend the commencement exercises at the State Normal School of which her daughter, Lucile, will graduate.” Lucile became the first Black student to earn a normal degree at UNC.

Commencement exercises were held on Thursday, June 8, at the Greeley Opera House. The program began with Mendelssohn’s “Fair Tinted Primrose” by the Ladies’ Chorus, followed by the invocation. Math teacher Mary Kendel sang Luigi Luzzi’s “Ave Marie” [sic]. Remarks by Katherine L. Craig, the state superintendent of public instruction and president of the State Board of Education, to the gra-uates were “received with much enthusiasm.” Richard Broad Jr., former mayor of Golden, chair of the State Silver Republican Central Committee, and trustee of the State Normal School, presented the diplomas to the graduates, at the conclusion of which the Ladies’ Chorus sang Macrirone’s “A Farewell.” Dr. Richard W. Corwin, a physician and member of the board of trustees gave the commencement address, followed the benediction.

More Stories

-

School Psychologists in Short Supply as Youth Mental Health Concerns Increase

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Greeley Educator, Alumnus, Honored with National Educator Award for Excellence

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Hey, Teach! Or Should That be Professor?

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Alumna Named Colorado Teacher of the Year

Este artículo no está en español.