It’s been a difficult month in Colorado, with two record-breaking wildfires devouring hundreds of thousands of acres of land, causing evacuations, unhealthy air quality and plumes of dark smoke rolling over the Front Range.

It’s not entirely unexpected, according to experts. Scott Franklin, Ph.D., a professor of Biology at the University of Northern Colorado, said that bark beetles damaging trees, drier and warmer weather events and vast availability of fuel from wood debris have combined to create the perfect storm this fire season.

“You can’t point at one thing and say it was the cause; it’s a series of events that has led to this,” Franklin said. “It creates problems for us and opportunities for wildfires.”

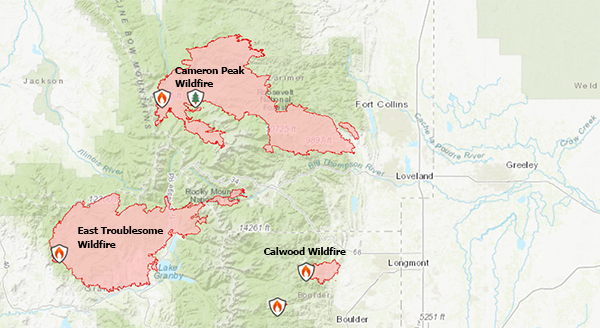

Above: Northern Colorado wildfires as of Nov. 3, 2020, from InciWeb

including Cameron Peak, East Troublesome and Calwood wildfires.

Despite the heavy snow that northern Colorado experienced in late October, more precipitation is needed to fully stop these ongoing wildfires.

“The snowfall has halted the wildfires for now, as it was so dry beforehand,” he said. “But, one storm won’t end them. We need to have a few more of these and then I think it’ll stop them.”

Franklin recounts studying the Fern Lake Fire that occurred in Rocky Mountain National Park in 2012 where that wildfire burned all the way into January, and “was burning underneath the snow” due to underlying dry fuels.

“If we don’t get more precipitation, then it means the fire season will become longer and more dangerous,” Franklin said.

When the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak wildfires do end, there will still be major concerns about how these fires impact ecosystems, including natural reforestation, wildlife and erosion concerns.

Typically, a forest can naturally regenerate itself to pre-fire conditions over 40 to 50 years, but this process may take longer due to impacts from the bark beetles.

Above: Pine cones from a lodgepole pine in Colorado.

Image from: Sean Buchan from Denver, C.O., U.S.A., CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

For example, lodgepole pines have adapted to living with wildfires. The tree’s seed-bearing cones are covered with a waxy coating to help prevent damage to the seeds during fires. Once the heat reaches a set temperature, the cones open and the seeds fall to the ground, which starts the process of natural reforestation in burned areas.

However, Franklin said he’s concerned that this natural seeding process may not take place because bark beetles can harm the seeds within the cones, inhibiting the pine’s ability to regrow the burned area.

There are steps that officials can take though. Franklin said that after the High Park wildfire that occurred in 2012, officials conducted aerial re-seeding because of a lack of seeds from the pines and other tree species, and he said that process seemed successful.

Experts are also concerned with an increased risk of erosion since the fires have burned off the majority of vegetation and trees. This loss of vegetation increases the risks of avalanches and landslides since root systems and topsoil vegetation typically help deter such events.

“What happens during this coming spring’s snowmelt and storms? Erosion of topsoil may increase and go into waterways, which can be toxic to aquatic systems,” Franklin said. “Also, avalanches and landslides will be more of a concern; the High Park Wildfire had around 120 landslides in the Front Range alone, which was a record.”

Some vegetation will quickly regrow in the spring, such as grasses and brush, Franklin said, since their underground root systems aren’t killed during a fire.

As winter arrives, wildlife face a decrease in the food supply, leading to starvation among some prey animals – which will in turn impact the amount of food available to predators, such as mountain lions.

With all of these challenges, Franklin said one possible solution to better suppressing wildfires includes forest thinning, where logging companies clear and sell forest timber. It can help decrease the amount of timber fuel available for future wildfires, but Franklin said it can lead to difficult discussions about how much timber should be harvested, and how it should be done.

Other efforts include prescribed burns in various locations to decrease the amount of timber fuel especially near populated areas.

“I wasn’t surprised by the wildfires we’re seeing and don’t think anyone who manages the forestlands was surprised either,” Franklin said. “We’ve been doing prescribed burning since the ‘80s, but it’s hard to do due to needed finances for it and to ensure that conditions are good. There’s a small window of opportunity in doing prescribed fires as we don’t want them to get out of control.”

Franklin’s research interests and fieldwork include disturbances caused by flood, wind and fire. Currently, Franklin is working with UNC graduate student Justin Yow as he researches different areas in southern and northern Colorado to examine how wood debris has changed over the past 25 years.

Yow’s research hopes to help foresters understand what, if anything, has changed with forest debris and how it influences wildfires in those areas.

Franklin believes wildfires and the overall fire season will increase in the coming years. He said that as more heat is being trapped in Earth’s atmosphere, that absorbed energy has to be released in some form, which usually results in larger and more intense storms. Such storms may not hold as much precipitation in them but can produce more lightning and wind events -- creating the perfect recipe for wildfires.

“It’s difficult to know for sure of climate’s exact role in influencing future wildfires,” Franklin said. “However, we will have the perfect setting for wildfires more often than what we’ve experienced in the past because the fire season is longer. In general, the chances of wildfires increasing, especially human-caused, will become more of a regular occurrence.”

Learn more:

- UNC’s Biology Program

- Franklin’s interview in a Bear-In-Mind Podcast episode, “A ‘Perfect Storm’ to Large Disturbance Events”

- Franklin’s Lab at UNC

- Previous story on Franklin’s research and teaching

—Written by Katie Corder

More Stories

-

Alumna Receives NSF Graduate Fellowship for Avian Conservation Research

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Novel and Interdisciplinary Research on Transgender Health

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Grad Students Researching Methods to Strengthen Mental Health Training in Rural Schools

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Doctoral Students Present Dissertation Projects in Three-Minute Competition

Este artículo no está en español.