Slither Into the World of Snake Venom Research

In this podcast, UNC Professor of Biology Steve Mackessy, Ph.D., goes into more detail about how he became interested in snake venom, his published and future research and other slithery topics.

September 7, 2018

If you're hiking in rattlesnake territory, then you're probably familiar (and terrified) of the rattling sound that alerts you to the nearby danger of a rattlesnake; however, one University of Northern Colorado researcher gets excited.

UNC Professor of Biology Steve Mackessy, Ph.D., studies snake venom — from its protein structures to the effects of the venom on other animals. He's also interested in its potential in the therapeutic world to fight against human diseases such as cancer.

In this podcast, Mackessy goes into more detail about how he became interested in snake venom, his published and future research and other slithery topics (full transcript is below the image gallery\). Also, see below for photos of his research lab and snake room at UNC.

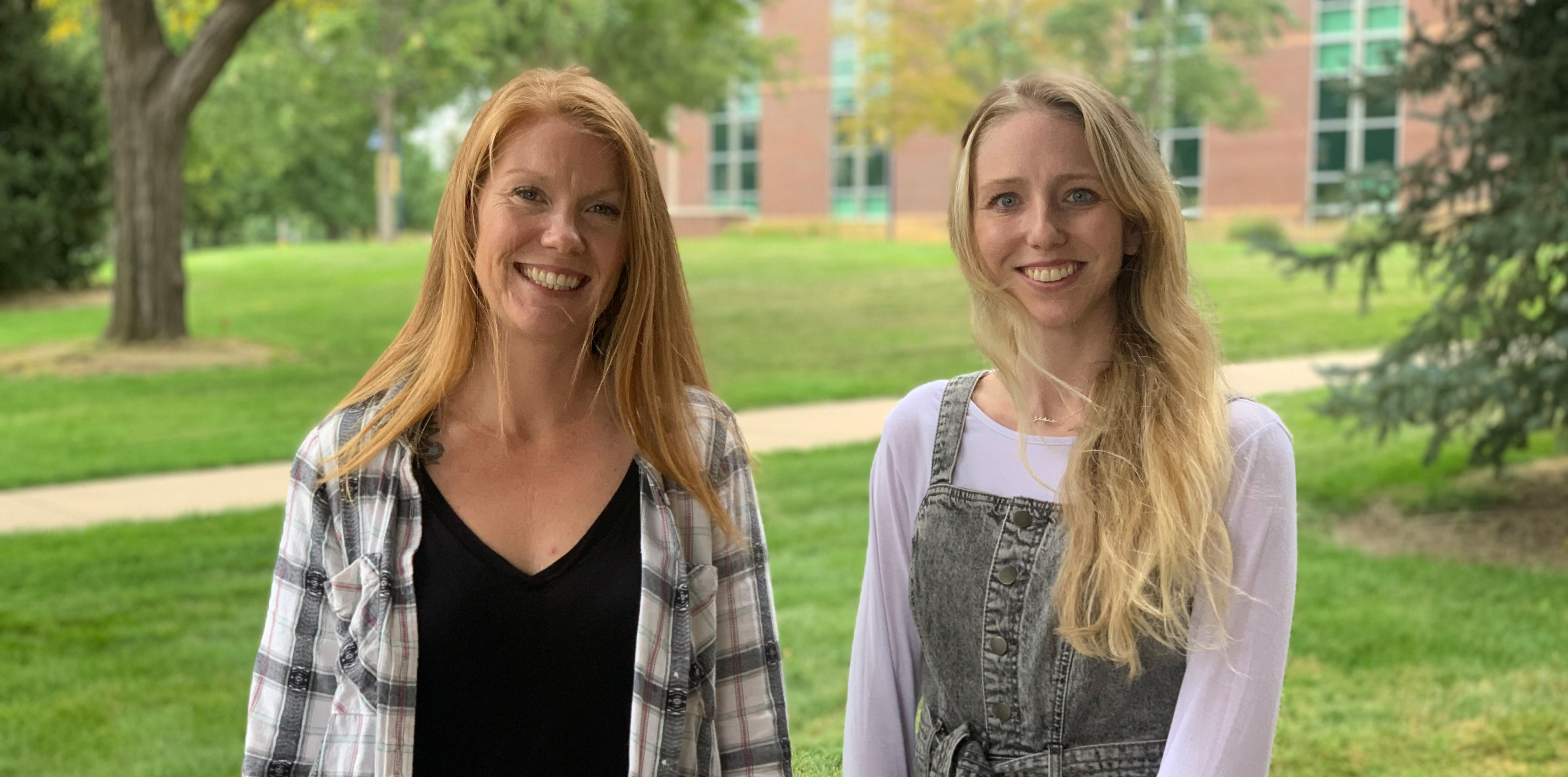

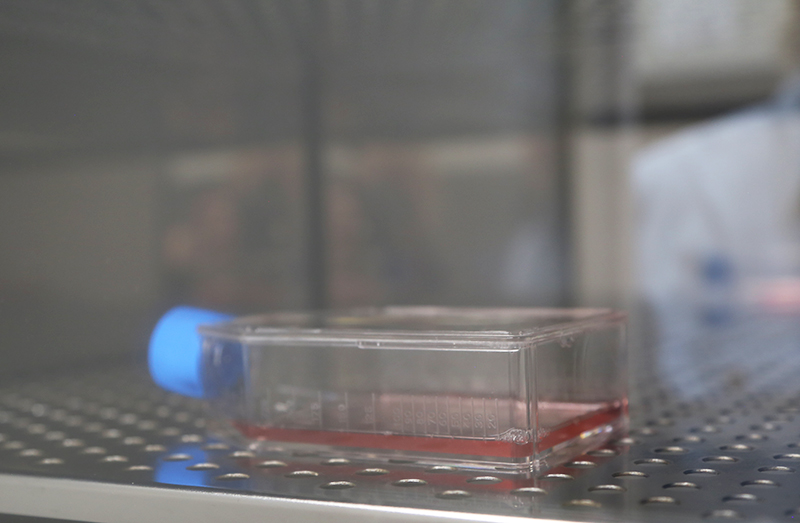

Venoms are being used to fight cancer, which is still currently in the testing stage. Pictured here are breast cancer cells that are used in Dr. Mackessy’s students’ experiments.

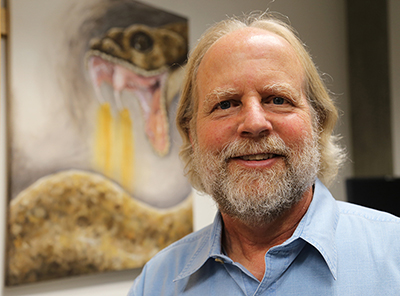

Steve Mackessy, Ph.D., poses in front of rattlesnake artwork painted by Olivia Davies, a recent graduate of UNC’s College of Performing and Visual Arts. Olivia also used mixed media, incorporating the shed skins of snakes (from our lab!) into many of her paintings, one of which is on display on the School of Art and Design home page.

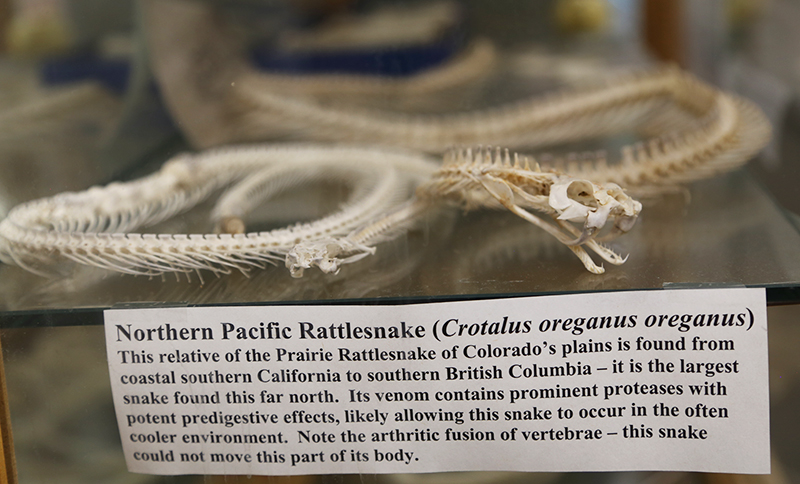

A skeleton of a Northern Pacific Rattlesnake outside of Dr. Mackessy’s office.

Dr. Mackessy was bitten by one of these as a teenager, which he talks about in the podcast.

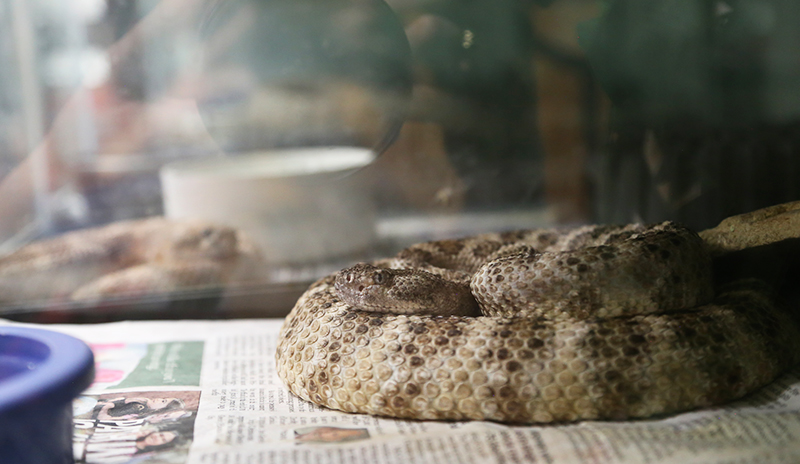

This is a Prairie Rattlesnake, the most common and abundant species of rattlesnake found in Colorado. It occurs across the eastern plains and into the mountains, to an elevation of around 9,000 feet in suitable habitat. It is also found in some parts of the Western Slope.

Dr. Mackessy poses with a nonvenomous Hognose Snake, which is one out of many snakes in his collection.

A closeup of the Hognose Snake.

A Trans-Pecos Copperhead snake. A peptide originally isolated from this snake’s venom is being used to combat Type II diabetes.

A female hybrid rattlesnake.

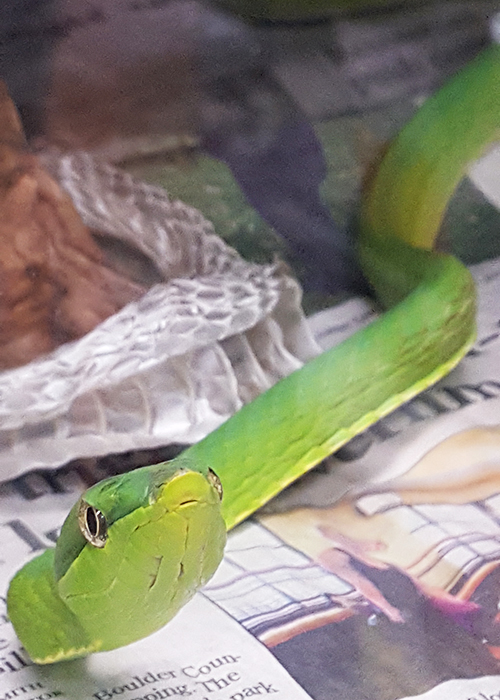

A Green Vinesnake from Suriname. This snake is a rear-fanged snake, meaning it has enlarged teeth in the back of its mouth. Venom from this species has a taxon-specific neurotoxin – this toxin is lethal to birds and lizards, their primary prey, but harmless to mammals.

He currently has approximately 100 snakes, both venomous and nonvenomous, in his lab at UNC. This is a Speckled Rattlesnake, which produces a venom with high amounts of tissue-damaging protein toxins.

A Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake, found in rocky areas of the southwest U.S.

A rattlesnake posing for a selfie!

A Midget Faded Rattlesnake, found in some drier parts of the Western Slope of Colorado. It is one of three species of rattlesnakes found in Colorado. No other venomous snakes are found in our state.

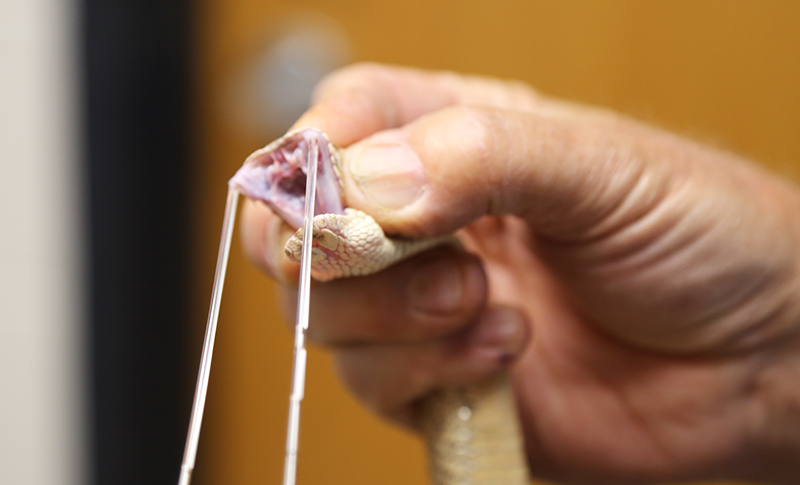

To obtain venom, first the snake must be safely removed from its container using a snake hook.

A Midget Faded Rattlesnake.

After grasping the snake’s head and exposing its fangs, venom is extracted by placing calibrated glass capillary tubes over the fangs. Cara Smith, a Ph.D. student in Dr. Mackessy’s lab, holds the tubes while Dr. Mackessy expresses venom into them.

This whole ordeal only takes a few minutes, and the amount of venom collected varies depending on size and species of the snake. For this Midget Faded Rattlesnake, 0.1-0.2 milliliters of venom is typical. This volume of venom will contain about 20 to 45 milligrams of dried venom.

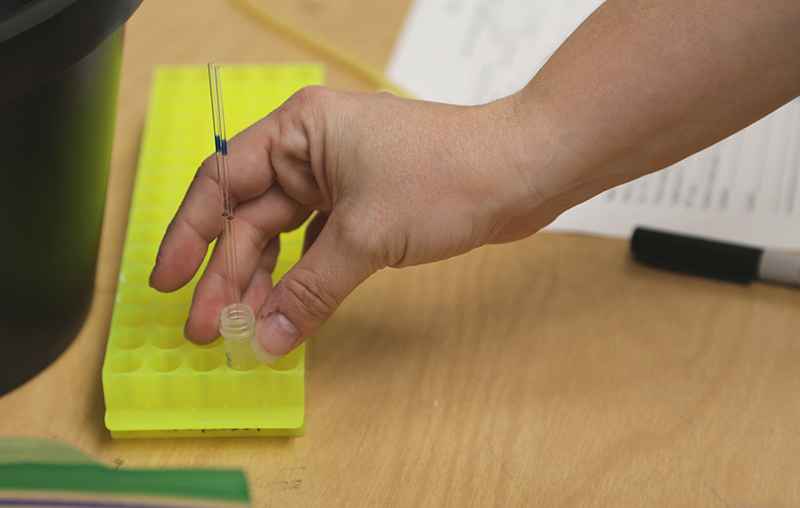

Afterwards, the collected venom is recorded and ready to go to the lab, where it is freeze-dried to preserve activities and stored frozen until used.

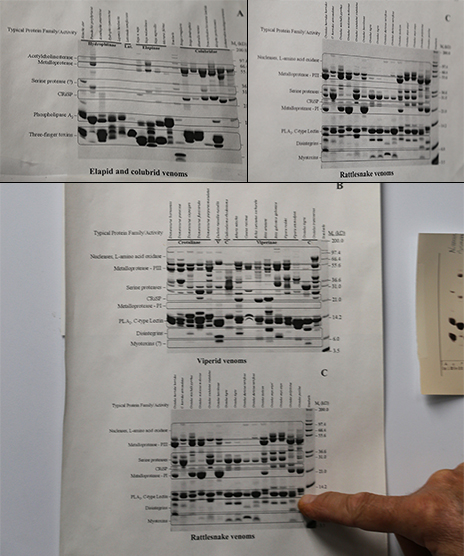

Collected venom can go through various tests and machines based on the specific purpose of the research. Pictured here is a gel electrophoresis apparatus that will provide a 'molecular fingerprint' of the venom.

These pictures of gels, stained after electrophoresis, show the 'molecular fingerprints' of many different snake venoms. In each diagram, the larger protein toxins are at the top, while the smaller toxins form bands at the bottom. Because Dr. Mackessy’s lab has worked with venoms for many years, we know that certain toxins form bands at certain places in the gel, allowing us to identify many protein toxins quickly, simply based on their band patterns.

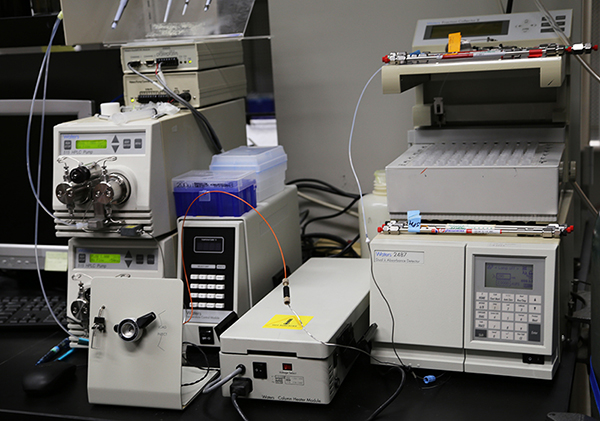

This machine is a high pressure liquid chromatography apparatus that is used to analyze the venom and to separate the various components of venom from one another.

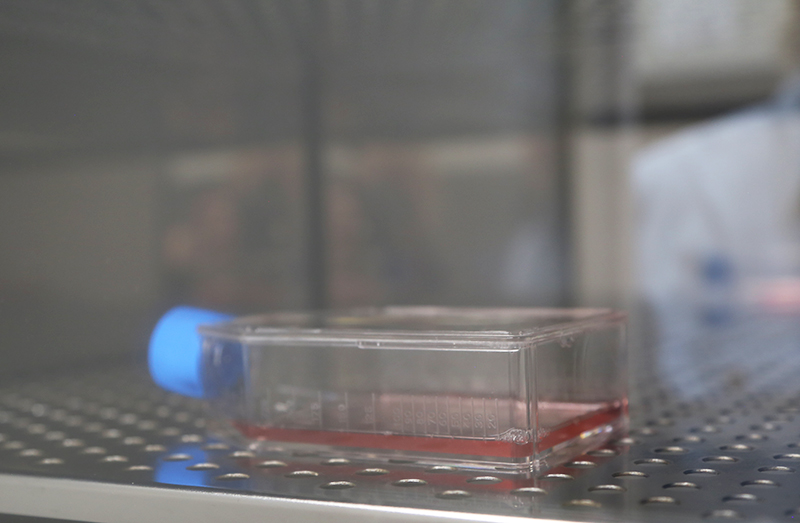

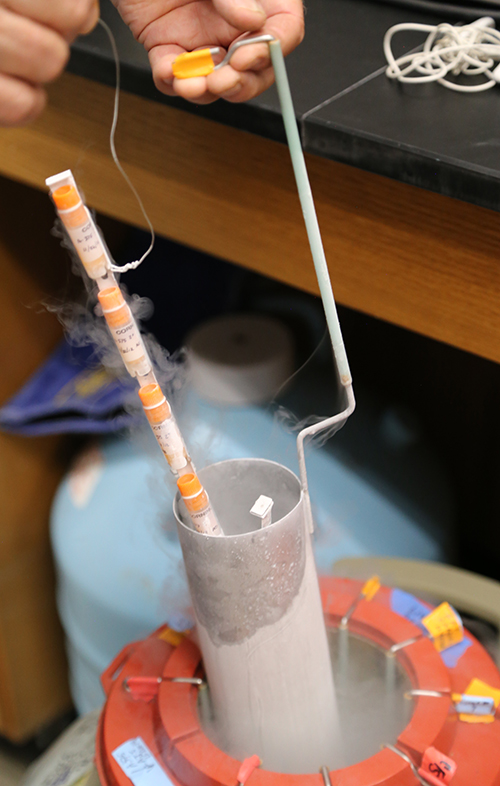

Dr. Mackessy shows a collection of cancer cells that are kept in liquid nitrogen – the extreme cold preserves the cells, and to grow them, they are brought to room temperature, added to nutrient media in a flask and incubated at 37 ˚C (~98.6 ˚F). They are then used in experiments with venom toxins to evaluate the effects on cell growth, cell survival, etc.

Venoms are being used to fight cancer, which is still currently in the testing stage. Pictured here are breast cancer cells that are used in Dr. Mackessy’s students’ experiments.

Steve Mackessy, Ph.D., poses in front of rattlesnake artwork painted by Olivia Davies, a recent graduate of UNC’s College of Performing and Visual Arts. Olivia also used mixed media, incorporating the shed skins of snakes (from our lab!) into many of her paintings, one of which is on display on the School of Art and Design home page.

Follow along with the full transcript below:

Hi, I’m Katie Corder, the creative content producer at the University of Northern Colorado. I sat down with Steve Mackessy, who is a professor of biology at UNC. His research revolves around snake venom, the types of protein structures found within the venom, and how the venom can be used to combat diseases such as cancer.

If you have a fear of snakes, then his locked lab that contains a variety of snakes from floor to ceiling may be somewhat of a nightmare. However, these animals should be conserved and respected not only because of their potential to assist our health, but because they don’t go out of their way to bother humans.

In this podcast, Dr. Mackessy goes into more detail about how he became interested in snake venom, his published and future research and other slithery topics.

Mammals, in general, are pretty fragile; it’s very easy as it were for a snake to knock things out of balance, and that’s exactly what’s happening with the venoms. So, when they inject the venoms, they’re injecting these kind of modified — they’ve evolved and diversified in the venoms — but they’re modified regulator compounds. So, they’re compounds that are very similar to what our bodies have in our blood to say whether or not blood is going to clot or not. And the snakes, when they bite you and inject that — and a lot of the rattlesnakes have a large amount of these thrombin-like enzymes as they’re called — when they inject that, they’re putting a lot of that regulator in at the wrong place and the wrong amount and the wrong time. And the effect is that just wreaks havoc with that very, very carefully balanced system.

So, all these different compounds are doing that simultaneously to a number of different types of systems. So, the prairie rattlesnake in our area has a toxin called ‘myotoxin A.’ It’s a small peptide, and that interferes with calcium balance inside of muscle cells. So, when that is delivered to a mouse by a snake biting the mouse, the mouse undergoes what’s called hyperextension. All its limbs are Teknik and straight out. Well, if you think about what a snake is trying to do, mice are pretty active little animals, so if you can stop it, and stop it just like that, that’s to the snake’s advantage, and that’s exactly what this toxin does: it causes the mouse, doesn’t kill it outright, but it causes the mouse to be essentially paralyzed almost instantaneously.

There are all these different proteins, some of them as I mentioned, affect the muscles, affect the blood, some of them affect the nervous system, and so you can get all of these different compounds in varying quantities in the venom from a single snake. But if you look at a cobra venom, and compare that to a prairie rattlesnake venom, the composition of those proteins is very, very different, and the overlap, which is the shared components of those venoms, is very minimal. In fact, the way cobras kill things and rattlesnakes kill things is fundamentally quite different, as well.

So, that gets back to the idea of what do we do if we get bitten? We have to use an antivenom that’s been produced in something like a sheep or in horses, and they make antibodies to all of these different proteins. Well, if it’s an antivenom that was designed to target rattlesnakes, it’s going to have essentially no affect against a cobra bite and vice versa. So now if we kind of distribute that across the globe, all the different venomous snakes in the various areas around the globe, we’ve got a very complex puzzle and problem to try to figure out and deal with so that someone that is in Indonesia or someone in India or somewhere in Togo in Africa, the kinds of species they encounter are very, very different, and the venoms are very different, as well. So again, it makes for an interesting puzzle on our end and an interesting medical challenge for people dealing with snake bites in those countries.

There can be as many as 100 different proteins in the venom from a single, individual snake. And so, we’re interested in what all those different compounds are, what they’re doing for the snake, what they might be able to do for us if we can purify them and use them as a drug or as some kind of a diagnostic compound.

A lot of what we do in my lab is get venoms from the snakes, take them apart and ask that basic question: Do they have compounds in them that are interesting, biologically? Interesting potentially therapeutically? Or just kind of cool proteins in general?

What’s some recent research of yours that’s been published?

We work on a lot of different aspects of venomous snakes and their venoms, and this summer has been a particularly productive summer as far as getting papers out.

This year, we had a paper earlier that dealt with the effects of particular toxin isolated from a venom from an Indian snake, and its effects on a particular type of colon cancer cell in vitro. We can culture cells in the lab; these are typically harvested from human cancers.

These cancers can be grown, and then we treat them with various compounds and look at the various effects on them. And snake venom in general are designed to kill things like other animals and break down cells and things like that, so just destroying cells without any kind of references is not all that interesting. But there are certain compounds that can induce cells that can go into what’s called programmed cell death or apoptosis, and if you can do that to problematic cells like cancer but not affect other cells, then you’ve got something that’s potential as far as a therapeutic and drug-development, and that’s what we’re looking for in some of these venom compounds.

We just got a paper published in a Genomics journal, and this is dealing with the genome of a type of garter snake — and this is a project that I was a contributor to, but it involved about 20 or 30 other people from all across the United States. And there’s a garter snake that lives in Oregon that feeds on very toxic newts, and these newts are poisonous, but the garter snake can handle that, and so there’s this very interesting co-evolutionary story that’s revolved around that snake and its predation. And now we have the entire genome sequenced and a lot of other aspects of its biology that we can understand by looking at its genome.

We’ve had some work with snakes from Mexico. In fact, colleagues that were working down outside of Mexico City collecting snakes and venoms down there a number of years ago, and we just had that paper published about a month ago in a journal Toxins. And that basically is talking about all the different types of proteins that are found in a venom.

What has surprised you the most from your research?

One is that when a rattlesnake strikes a mouse, they’re what are referred to as a strike-and-release predator. So, rattlesnakes will sit coiled by a trail, a mouse trail, or even a human trail, because mice run up and down that. They’ll sit there coiled for hours, days, maybe even a week or so — very patient animals — waiting for a mouse to come by. A mouse comes by, they strike it, they bite it very quickly, the whole contact time is less than half a second. The mouse runs off a little distance and then falls over and dies. Well, the snake can’t follow where it’s gone and, depending on how resistance the mouse might be to the venom and the placement of the venom and how much the snake injected, it may drop immediately, or it may go several meters or maybe five meters away, and so now the snake has to find it.

Well, they have an uncanny ability to track that, and you think, “Well, that makes sense. When a mouse has been envenomated, it’s physiology is going crazy. It’s probably giving off all sorts of weird scents and stuff.” But, if you think about it, the snake is following a chemical trail, and mice have been running up and down that same path, all day and last week and everything else, so this chemical path is a mixture of different things, and somehow the snake is able to follow that specific track that leads to the envenomated mouse, and dinner time!

We’ve been interested in that for a while, and a colleague down at CU-Boulder has done incredible amounts of research along that line for many, many years. It’s called strike-induced chemosensory searching. So, after a snake strikes, it undergoes tongue flicking, and you’ve probably seen a snake tongue flick, and that’s actually loading up chemical scents on the tongue, and some of those actually tell it where the envenomated mouse went.

If it’s injected into the mouse, then the snake can discriminate it very statistically, very significantly higher than it would go after a non-envenomated mouse. So, we decided to take the venom apart and ask the question, “Okay, is there a particular molecule, or a suite of molecules, that allows it to do that?” And the answer is yes. There’s one little compound in there called a disintegrin molecule, and it’s that one alone that when you inject the mouse, it allows the snake to follow it with a high degree of fidelity wherever it goes.

There’s several interesting things about the disintegrin. One is it’s not toxic particularly. So, if you inject a live mouse with it, it doesn’t really do much to it. So, it’s a nontoxic toxin.

The other thing is that this has been a very interesting molecule for pharmacologists, and has been for a number of years now, because it also has a very potent effect on cancer cells. And cancer grows from a single mass into a tumor, and then cells begin to metastasize and move away from that tumor and that’s when it becomes very dangerous because then you can set up tumors throughout your body, and these various different types of cancers can wreak havoc with us.

Well, if you give a mouse that has been infected with breast cancer, for example, if you give it disintegrins from a particular snake called the copperhead, then those tumors don’t liberate cells, they don’t form daughter tumors anywhere near as great as the control animals do, and the tumor sizes are much smaller, as well. There’s been a lot of interest, including in our lab, in looking at disintegrins from different types of rattlesnakes, and other vipers, and asking, “Can this one be used for this specific cancer or that cancer to treat metastatic activity?”

One of the other things that we’ve been looking at has been the effects of what we call taxon-specific toxins. And what these are, and the first one we found it in was a snake called the brown treesnake. This is one that’s caused ecological disaster for birds in particular, but small animals in general, on the island of Guam in the south Pacific. That snake produces a venom with a toxin that’s a significant amount of the venom, that when you purify it, and you look at its actual structure, we’ve actually crystallized it, and looked at its three-dimensional structure, atom-by-atom, and it looks almost identical to a toxin that’s found in cobra venom that would kill you and I very nicely.

This toxin has no effect on mammals at doses 100-times higher than it takes to kill a lizard or a bird, so it’s a lethal toxin for lizard or a bird, but it’s harmless for mammals. That’s pretty cool. And that begs the question, “How in the world does that work?” We know that part of it has to do with just the sequence of amino acids, these are proteins that are made up of individual amino acids, and there’s a particular part of a molecule; they’re called three-finger toxins because they look like three fingers pointing down like this, and the middle finger actually interacts with particular receptors in our body that are associated with the way nerves and muscle communicate.

And so, it takes the place of a communication molecule called acetylcholine and blocks the binding site for acetylcholine. It’s a big protein, so once it gets in there, the little molecule can’t get there at all, and that receptor’s dead, so your nerves can say, “Contract! Contract!” And your muscles say, “Huh? I can’t do anything.” So, if you’re bitten by a cobra, paralysis is an early symptom, and if your diaphragm and your frantic nerve are compromised, you stop breathing, and that’s where people get into trouble with bites from cobra and kraits and things like that.

This toxin from the brown treesnake should do the same thing, but it doesn’t to mammals, but it does to birds and lizards. We’re trying to chase down what’s going on there, and in the process, we’ve also looked at a number of different snakes. Now some new-world snakes — so new-world tropics: Central America, South America — and it turns out some of them have a toxin that’s very, very similar. Which is kind of interesting because the brown treesnakes and the new-world snakes are very, very distantly related, but they’re both using the same basic strategy to target their favorite foods, which are lizards and birds.

These are natural compounds that have evolved, in some cases, over tens of millions of years, sometimes hundreds of millions of years, for things like jellyfish and snails, cone snails, and so, the potential for some really specific interactions with minimal to no side effect is really quite high. And if we can’t use the molecule directly, we have some really good chemists these days that can tweak that molecule around and make it into something that’s potent, maybe smaller, and even more specific, so we can use the natural compounds to inform us on new drug design and that is across the board.

I like to say lizard spit is being used to treat type II diabetes, so there’s a drug that’s been derived from Gila Monster venom, and it’s very, very effective in controlling some types of type II diabetes for some people. It’s been like a miracle drug for some people.

So, I must assume you’ve dealt with a snake bite in your life. Have you?

I was bitten once when I was 15 on April Fool’s Day, and that was a baby southern Pacific rattlesnake that a friend had brought over to my house. I picked it up with a snake hook like you’re supposed to, then I decided to hold it by the tail like you’re not supposed to, And the snake was only about a foot long or less, and snap! Just like that it flipped around and hit me in the left hand. And so, I got to spend the next six days in the hospital.

Got there within 20 minutes of the bite happening, and then I sat around for four hours in the emergency room waiting for them to do something. And I watched my hand swell, and it just started to engulf my fingers, and then moved up my hand and then moved up my arm, and it eventually swelled my arm all the way up into the shoulder, about double, and my fingers were like little sausages. I could barely move them. And they gave me some antivenom and kept me in the hospital for observation, and I was in there for a total of six days, and if you’ve been in the hospital within the last 10 years you know that all of a sudden breaks the bank. In fact, antivenom in the U.S. is outrageously expensive, and it ranges from a low price of about $2,500 up to as much as $10,000 per vial.

When I was even a preteen, I was kind of interested in scaly things. I grew up in southern California, about three blocks away from the base of the San Gabriel Mountains, and we didn’t have much in the way of money or opportunity, so we would just go hiking. So, we’d occasionally see snakes up there, and I got interested in them.

I found out from a friend about a guy who was selling snakes to zoos, so he needed somebody to help clean cages. And so, as a 12, 13-year-old, I was doing that. And then he and another fellow opened a business, so all through high school my job was taking care of a room about this size that had cages on all four walls to the ceiling of all the most venomous snakes around the globe that you can imagine: spitting cobras, mambas, king cobras and things. I was about 17 when I was chased out of the venomous room by a 14-foot king cobra, and that was interesting. It made me consider, “Hmm, I’m getting $3.50 an hour here, maybe it’s time for the boss to take care of this problem.”

So, what can people in Colorado do to avoid being bitten? And if they are bitten, what should they do?

In Colorado, we have a total of three rattlesnakes only: prairie rattlesnake, midget faded, and several other western rattlesnakes that were all included in this one species package that was called the Western rattlesnake, that’s been broken up now.

If it’s between late March or Early April and late September in Colorado, those are generally the snake activity months, so that’s when you can expect them to be above the surface.

The main thing is keep that in mind, and if you’re going out hiking on trails, you should really have protective gear on of some sort. Now, when it’s hot it’s nice to wear open shoes and shorts and things like that. When I take my students out on field trips, specifically looking for these animals, I said I don’t care what you wear above your waist, but you need to have jeans and some kind of boot and that keeps you much safer.

Common sense, being aware that snakes might be out in the area, knowing a little bit about their habits: they do like to sit in a coil right next to trails, and so there’s a possibility as a person goes by with a barefoot, it might look like a nice, warm little mouse sort of thing, and the snake could strike at that. Obviously, if you step on it, then the snake is going to act defensively, and you could be bitten in that sort of fashion. But in the U.S., the greatest risk of snake bite comes from intentional handling, and somewhere around 75 to 80 percent of the bites are to males, and the majority of those bites are to the hands, so that tells you it was mostly not an accident.

If you are bitten, the adage is ‘time is tissue.’ And so, what they’re referring to there is the fact that snake venoms progress until the bite doesn’t have its effects instantaneously. Although. when I was bitten. I could tell almost immediately because it felt like something irritating under the skin, like fire under the skin essentially. And so, generally speaking, most rattlesnake bites will have something like that where it’ll be somewhat painful almost immediately, locally. But it will get worse over time, and so the faster you can get to the hospital, the better.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

One thing I always like to put out there also is the aspects and the need for conservation of these animals. If you can bring these animals that are otherwise seen as varmints and pests and vermin and things like that, if you can bring them into the realm of experience of people, then all of a sudden they know a little bit more about them, and they can appreciate that they actually have some pretty interesting qualities.

The fact that they can be quite common means that they’re going to take out a lot of rats and mice and other rodents, and of course, those animals are often vectors for diseases that we can get. Deer mice, a cute little deer mouse can bring the hantavirus to your house, that’s not so good. These things are very important for the checks and balances that are in natural systems, and if you wipe them out, all sorts of unpredicted, or unseeable, changes can occur, and often times, they’re not what we’d think; they’re not going to be to our advantage.

So, I try to communicate that to people and get them an appreciation for these animals that, up close, are dangerous, but at a distance, they’re interesting to see. And if you leave them alone, for the most part, that’s what’s going to happen, they’ll leave us alone.

Read More

—Produced by Katie-Leigh Corder

More Stories

-

Alumna Receives NSF Graduate Fellowship for Avian Conservation Research

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Novel and Interdisciplinary Research on Transgender Health

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Grad Students Researching Methods to Strengthen Mental Health Training in Rural Schools

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Doctoral Students Present Dissertation Projects in Three-Minute Competition

Este artículo no está en español.