In 2014, tragedy struck when a child was discovered deceased by her mother in Vancouver, British Columbia. The evidence discovered at the crime scene proved to be quite different than what law enforcement is typically used to dealing with: snake venom.

In order to accurately close the case, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police needed an expert to help analyze samples recovered from the crime scene, and they quickly contacted Steve Mackessy, Ph.D., a professor of Biology at the University of Northern Colorado.

“I was first contacted by them in the summer of 2014, and at first, I thought it was

a joke … somebody trying to prank me or something like that,” Mackessy said. “But

then, as I listened to the message, it became clear that there was something a bit

more substantial to it.”

“I was first contacted by them in the summer of 2014, and at first, I thought it was

a joke … somebody trying to prank me or something like that,” Mackessy said. “But

then, as I listened to the message, it became clear that there was something a bit

more substantial to it.”

Mackessy was sent evidence from the crime scene that included a dead snake, shed snake skins and bodily fluid samples from the victim. He and two of his doctorate students, Cara Smith and Anthony Saviola, spent weeks to months analyzing all of the evidence in order to give accurate results to Canadian law enforcement.

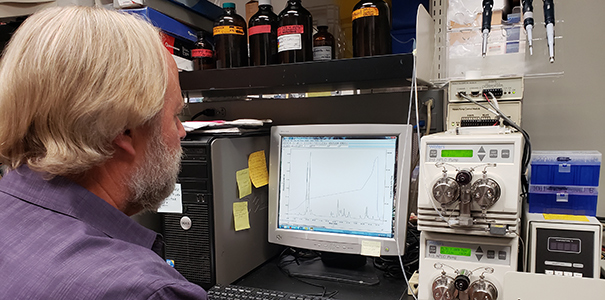

“We used a variety of different types of molecular and protein-chemistry techniques to ask the questions: what are these species of snakes that are involved here and are any of them potential sources for the venoms that seem to have been involved in a crime?” he said.

In late summer, an arrest was made as well as a confession shortly after, and the sentencing will take place in early October. Mackessy was central in closing the case.

“It is highly unlikely that the investigation would have been successful without the hard work of Dr. Steve Mackessy, and his team at the University of Northern Colorado,” said Sgt. Doug Trousdell of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who worked with Mackessy. “His conclusions were invaluable to the police in advancing the investigation and invaluable to the community in ultimately coming to understand what caused Aleka Gonzales’ death. We thank him, and his team, for their substantial contributions to this complex and difficult file.”

In the below podcast, he goes into more detail on the tragic crime and how his contributions to the forensics were central in closing the case.

Follow along with the podcast's transcript below:

Hi, I’m Katie Corder, the creative content producer at the University of Northern Colorado. I sat down with Steve Mackessy, a professor of Biology at UNC, to discuss his involvement in analyzing snake venom and other samples that were from a crime scene in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 2014.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police contacted Professor Mackessy about his expertise in snake venom and how he could help them by analyzing the forensics of the case, which included snake venom, shed snake skins and bodily fluid samples.

In this podcast, Professor Mackessy goes into more detail on the tragic crime and how his contributions to the forensics were central in closing the case. This shows how essential science is in forensics and assisting law enforcement in closing cases.

Can you sum up the case for me: Who did it involve? When and what was the evidence, and where?

This is an interesting and tragic case that occurred in the Greater Vancouver area of British Columbia, and the short version of it is there is a fellow in that area that believed one way to stimulate his immune system was to give himself injections of venom. He also had a girlfriend with a young daughter, and as far as we can tell, thought that it might be a good idea to also apply the same treatment to this little girl, and she was only a couple of years old. And, tragically, this ended up with the little girl dying from what we believe is rattlesnake envenomation, not from an actual rattlesnake, but from the venom that was administered to her. The date that it occurred was sometime in early 2014.

The investigation has been ongoing, and there are many parts in the middle phase that I'm not privy to the details, but apparently, within the last month-and-a-half things have come to a head. They arrested the man, charged him formally and he has pleaded guilty to the charges. And so, we're just waiting for the course to figure out exactly what to do next as far as sentencing.

Can you describe your involvement in the case, and how the Royal Canadian Mounted Police found and contacted you?

I was first contacted by them in the summer of 2014, and we were actually in the field out over on the western slope, had been in an area with no reception for several days, came into Grand Junction for lunch, etc., And I checked my emails and voice messages, and there was a message, a voice message, from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. And at first, I thought this was a joke, you know, somebody who's trying to prank me or something like that. But then as I listened to the message, it became clear that there was something a bit more substantial to it. I ended up calling back the officer and talked to him and got basically a first look at what the details were and what they were hoping to find out. And so, it proceeded from there.

Describe what you discovered with the snake venom in the murder. What type of snake or snakes or venoms were involved? How was that venom or were those venoms used in the murders, and how did you conduct your research on that?

Basically, we were sent a series of samples and these samples ranged all over the place from a dead, frozen snake that we were asked to identify to about 25 or 35 samples of shed-snake skins.

The dead snake — that was easy to identify morphologically — was a Mojave Rattlesnake. This snake produces a particularly potent venom. And so that would be something that small amounts could easily kill a human, and in fact, sometimes do in places like Arizona and New Mexico.

The other snakes, the shed skins, this man had a collection of snakes at one time. The arresting officers only found, I think, three or four living snakes at the time. And these were two different rattlesnakes: Western Diamondback and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes. But the shed skins, they were from about 10 different species of venomous snakes and also at least one non-venomous snake, a Boa Constrictor. But they included things like: cobras, a variety of different species of rattlesnakes, and I think there were one or two vipers from South America, as well. Now, none of these are legal for an average citizen in Canada to possess without specific permits, and so that in and of itself was an issue.

And then, there were also from the deceased, samples of blood and samples of urine. There were also, I think, the last couple of samples that they asked us to look at were syringes found at the scene, and they were curious as to whether or not these might contain residues of venom. So, a variety of different types of samples. It turns out that when a snake sheds its skin, there's still quite a bit of cellular matter that's left in it and that actually preserves quite a bit of DNA.

So, we can take a little piece of shed skin from the snake and derive enough DNA to do identification reactions — basically, PCR-based reactions that are looking for molecules that would be a signature of species one or two or three. And so, we were able to identify, with a high degree of probability, all of those different samples.

The one snake that was the entire thing, we could simply look at it and identify it from morphological features, that wasn't a problem. The other samples were a lot more problematic. And so, we tried a variety of different types of protein chemistry and proteomic techniques to try to analyze all those samples for the presence of venom or venom-based materials. Now, venoms are primarily proteins and peptides, and so, we can use a variety of immunological tools, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, for detecting the presence of pretty small amounts of material, and by pretty small amounts, we mean something on the order of a billionth of a gram of venom per … probably something like a microliter of blood, so a tiny drop of blood. So, it’s a very sensitive technique for picking up these kinds of materials.

We used a variety of different types of molecular and, like I say, protein-chemistry techniques to ask the questions: what are these species of snakes that are involved here, and are any of them potential sources for the venoms that seem to have been involved in a crime?

That is interesting, and how long did it take you to go through all of those samples and everything?

Some of the samples we were able to process, the majority of them — I should say — within about three weeks to a month. And then, because we kept getting equivocal results with some of the things like the syringes, the urine sample and the blood samples, I tried a variety of different techniques to increase the sensitivity, increase the specificity of detection on those. And so, that went on for several additional months just trying to refine that as we could.

How did your contributions to the forensics of this case help solve the case, or at least lead the detectives in the right direction?

Again, we don't really have access to the specifics of what was discussed during the trial and that kind of thing, so, I'm not 100% sure other than the officer with whom I interacted the most just mentioned to us that our contributions were central in getting the conviction on this man. Now, it may have been simply by identifying all the different species of illegal venomous snakes that he housed that he felt as though his options had become limited as far as getting away from this crime, getting off from being charged. All in all, if it seems to be that these different analyses did bring the case to closure and bring it to a head.

Excellent. Do you have any additional comments about the case or your involvement in the case or anything in general?

Well, hopefully, actually we won't get many calls like this to discuss how we might detect venom in deceased blood or something like that because, although forensically and biologically it's interesting, and it represents a bit of a challenge to see if we can actually come up with methods, etc., to detect very small amounts of these toxic materials. In the end, what we're talking about is some human tragedies and such. And so, hopefully, we won't see too much of that occurring. Snakes have a bad enough reputation with a certain subset of population anyhow; they don't need any more adverse advertisement like that.

Excellent. Thank you so much.

Sure. You're welcome.

—Produced by Katie-Leigh Corder

More Stories

-

Alumna Receives NSF Graduate Fellowship for Avian Conservation Research

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Novel and Interdisciplinary Research on Transgender Health

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Grad Students Researching Methods to Strengthen Mental Health Training in Rural Schools

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Doctoral Students Present Dissertation Projects in Three-Minute Competition

Este artículo no está en español.