Article

January 12, 2021

Written by Katie Corder

UNC Expert: The Capitol Riot and its Lasting Impacts

On January 6, supporters of U.S. President Donald Trump stormed the Capitol in Washington, D.C. As people not only in the U.S. but around the world try to understand the event and its ramifications, UNC Professor of History Fritz Fischer, Ph.D., offers context from a historical perspective.

On January 6, supporters of U.S. President Donald Trump stormed the Capitol in Washington, D.C. As people not only in the U.S. but around the world try to understand the event and its ramifications, University of Northern Colorado Professor of History Fritz Fischer, Ph.D., offers context from a historical perspective.

“What happened on January 6 was an unprecedented insurrection; it was a riot, and it’s debatable whether we can call it a coup, but it resembled a coup,” Fischer said. “The reason we are so shocked and appalled is because what happened has never really happened before.”

Fischer, whose research includes 20th-century U.S. political history as well as teacher education, also said that people are comparing the January 6‘s events to the War of 1812 when Great Britain invaded the U.S. “But it was a totally different thing because in that case, it was a foreign country that attacked our capital city and burned it to the ground.”

History — and recent events — can help contextualize what happened and why. And it can provide understanding for the reactions people experienced during and after the riots.

“The riot itself wasn’t the most shocking thing; the most shocking thing was that it was our own president who directed an attack on our Congress, and that has no precedent in U.S. history and surprisingly few in world history,” he said. “To have one part of our government attack another part of the government is totally insane, and it was dangerous and antithetical to any traditional understanding of how our government should work.”

Fischer shared historical context and background for the events we are seeing unfold in the Capitol:

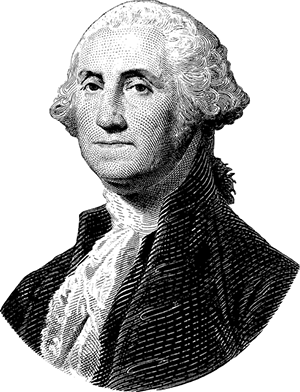

Newburgh Conspiracy, 1783

In the 1780s, the newly formed U.S. was still in the midst of the Revolutionary War with Great Britain. The then-Confederation Congress had not paid the Continental Army for some time, which caused unrest among the troops and officers. Eventually, this led to the army planning to march on Philadelphia, the city where the capitol was located at that time and demanding their pay.

General George Washington defused the situation in the end, which led to saving the fate of the new government.

“Washington got wind of this, and it’s a very famous scene where he stands in front of his officers who were going to go with the troops to Philadelphia, and he pulls out his spectacles, puts them on and apologizes to the officers by saying something to the effect of, ‘I’m sorry. I have actually gone nearly blind in the service of my country,’” Fischer said. “And what that suggested right then is what sources say ended the conspiracy: Washington was saying this is what we give for our country and it’s not about the pay. He and his troops weren’t getting paid or receiving credit for their actions during the war, but, in the end, their ideas were bigger than those complaints.”

Election of 1876

During the election of 1876, election fraud ran rampant. This election event was important because the law on how the process for accepting electoral college votes stemmed from it, which is the law that members of Congress use to object to electoral college votes.

The 1876 election centered on Reconstruction, the time period after the Civil War when the federal government sought to transform southern society including increasing rights for the newly freed African Americans. Many southern whites resisted and desired a return to something that resembled the pre-Civil War era of government by “excluding African Americans” in political processes.

During the 1876 election in the South, many people, especially African Americans, were prevented or intimidated from voting, and ballot stuffing and other questionable acts occurred from both political parties in an attempt to sway election results. A few southern states sent competing sets of electors to Washington, which required Congress to form a bipartisan Electoral Commission in order to settle the 1876 election as well as provide a precedent for future debates.

Civic Religion

There are numerous places, monuments and historically relevant symbols that were built throughout U.S. history that many Americans view as deeply rooted in the U.S. government’s foundations, such as the Lincoln Memorial, the Capitol and many others. Many analysts described the insurrectionists who raided the Capitol on January 6 as “desecrating” the building, which has such a connection to the nation’s overall history and government.

“There are numerous aspects of American history and the American governmental system that many Americans take as a kind of civil religion, and many of the words that people used on Wednesday, such as desecration, show how many Americans felt about an attack on the Capitol,” he said. “There were a number of symbolic aspects of what happened on January 6 that are especially jarring, symbols in direct opposition to the beliefs of this American civil religion.”

Fischer listed examples of such “jarring” symbolism including photos of participants carrying the Confederate battle flag, pro-Nazi clothing, the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag and others.

Fischer said this “American civic religion” is the difference between this and other riots that have occurred, because having such symbols considered anti-American in a place that is deeply rooted in American values and history was “hurtful to many.”

“Stop the Steal” Campaign

When the mob broke into the Capitol on January 6, Congress was in session in the process of certifying the electoral college and 2020 election results. Many chants and signs from the mob included “Stop the Steal” – a movement that, built on unsubstantiated accusations made by President Trump, believes the 2020 election results were false, along with other conspiracy theories.

“States worked hard to prevent election fraud, and, because of their efforts, there is no evidence of widespread fraud; however, the rioters apparently believe that the only legitimate government can be one that they support, which is clearly a problem,” Fischer said. “From the point of view of a historian, one of the biggest problems stemming from this is the idea of the need for evidence to create an argument. President Trump and his followers created their argument, which is that they should win and, therefore, they searched and searched for evidence to support their argument.

“One of the central ideas that I teach as a historian is that it has to be the other way around: First, find the evidence and then create the argument. The phrase that I use with my students is ‘there has to be a there … there,’ or, in other words, there must be something to work from. You can’t just come up with an argument, narrative or story, and then find the evidence to support it.’ And in this case, they have no evidence to support it.”

Black Lives Matter Protests vs. Insurrectionists

Another topic making headlines in relation to the January 6 events compares the amount of force used on the pro-Trump mob versus a far larger number of troops and more force used when confronting Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters in the past.

“In some ways what happened has heightened the lament of those who support the Black Lives Matter movement because of the difference in the way those protesters were treated versus the rioters,” Fischer said. “There’s a series of divisions and wounds that were potentially opened larger and are going to be more difficult to heal.”

How to Teach Controversial Topics in the Classroom

Many UNC alumni are educators, and some of them have reached out to Fischer and his colleagues for advice on teaching subjects like social studies, civics or history in K-12 schools during such a chaotic, divisive time.

According to Fischer, the “key is to always keep this historical method” upfront where you teach using the facts as well as how to find appropriate evidence online and use it.

“We must start with evidence because that’s what historians do; social studies teachers don’t teach myth, we teach history, and it’s rooted in evidence,” he said.

Fischer recommends that teachers be honest, unbiased and transparent about the January 6 events and says that it’s “so important that teachers make clear that they’re not stating an opinion, and that, instead, they’re using the historical method and sticking to the facts” regarding how the U.S. government works based on the Constitution.

“The idea that America is exceptional, meaning the best, is not what social studies teachers should be teaching. They should just say what happened: some of it was good and some of it wasn’t good or exceptional, and in the case of Wednesday’s events, it wasn’t good,” he said “The largest number of social studies teachers in the state have graduated from UNC, so it is a central part of our mission and a central issue that a number of our graduates and current students have to grapple with in the future.”

As time moves on and factual information is gathered and analyzed, the events of January 6 will become clearer in terms of planning, motives and short- and long-term impacts on American society and its citizens. Fischer believes this event is something that we can learn from as we move forward.

“The past is a mirror that we can look into and learn and make judgements from, and, in my personal opinion, because it was such a stark and jarring event, it is going to stay in people’s memories, and, therefore, have an impact.”