A Place in Colorado History

Professor George Junne’s wide range of research explores African-American success and resilience across the years

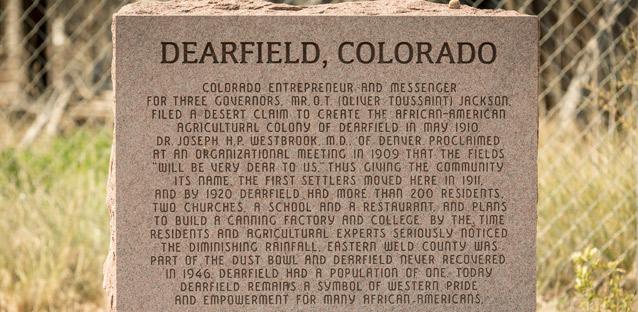

East out of Greeley on U.S. Highway 34 along the South Platte River, the geography is wide and open, with farmland stretching toward the eastern Plains. About 25 miles from Greeley and 80 miles north of Denver, you’ll find the remnants of Dearfield.

Dust rises in the heat of late August as UNC Professor of Africana Studies George Junne walks along the dirt road, past several gray and weathered structures that remain from the town. Birds have made themselves at home in the old buildings, and their music carries over the rural quiet as Junne tells the story of the people who lived here.

In 1910, in hopes of establishing an African-American community, seven families (mostly from Denver) began to build lives, frame homes and plant crops here. Over the next 20 years, the small settlement grew to a population of 200–300 residents, with two churches and a school, restaurant, dance hall, market and gas station. Junne says the residents, with little previous farm experience, surprised and impressed local farmers with their accomplishments. Then the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl devastated the fledgling community.

These building shells hint at the story, but the community’s hopes and plans are more tangible back at UNC, among fragile artifacts like letters, photographs and newspaper articles.

“The people of Dearfield wanted to have their own homes, their own land. They wanted to make it out here,” Junne says. He uses the remaining fragments of Dearfield to tell their stories. “There’s so much history out here on the Plains,” he says.

A writer, scholar and teacher, he has published six books and more than 50 book chapters and articles on periods ranging from the Civil War and emancipation to the Harlem Renaissance and Colorado’s participation in the civil rights movement.

Junne, who came to UNC in 1999, has traveled with students to Egypt, worked at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul as a visiting professor during summers since 2000, been honored for his discoveries as an amateur paleontologist, and been interviewed as an expert in USA Today and for various publications and films.

Last year, he was interviewed and filmed for an award-winning PBS documentary called Clara: Angel of the Rockies. One of the first African-American women to live in Denver, Clara Brown was emancipated from slavery in Kentucky in 1858 and traveled west hoping to find her four children, who had been sold years before. She went first to Missouri, then walked most of the 700-mile distance from there to Colorado. In Central City, she established a laundry business and invested in mining claims. With a deep sense of community and a strong Christian faith, Brown sheltered those who were ill or homeless, gave money and time to community churches and became known as “Aunt Clara.”

By the end of the Civil War, she’d saved $10,000 and returned to Kentucky, still trying to find her children. Unsuccessful, she paid for the travel of some 16 freed men and women to come to Colorado, and later used a large part of her wealth to send African-American women to college and help others settle in Colorado. After searching most of her life for her surviving daughter, Eliza Jane, Brown reunited with her daughter at the age of 82. She died in 1885, and an estimated 400 community members and civic leaders (including Denver’s mayor and Colorado’s governor) attended her funeral.

“Clara Brown is a good example of the strength of black women. This woman, who did not have an education, helped shape the Black American West,” Junne says. “You have a woman who comes from being personal property to being a successful businessperson. And she did it with basic Christianity. Her house was open to anybody wherever she lived.”

As he uncovers stories about African-Americans like Dearfield residents and Clara Brown, Junne shares his findings with his classes at UNC, and students are often surprised.

“Black history is American history as well,” he says. But he explains that it’s history that isn’t always taught in elementary, middle and high schools.

“There is this sense that black people didn’t do very well. Black people could own hotels and businesses and so forth — that’s some of the success people don’t know about,” he says.

Back in Dearfield, Junne smiles as he talks about a group of elementary students who travel here from Denver every year. The children walk the dusty road with papers and pencils in hand, taking notes as Junne tells them about the people who lived here and worked hard to make the place their own. In that moment, a century after the first families arrived in Dearfield, it is a place that still belongs to them.

–Debbie Pitner Moors