In the wake of shattering earthquakes and devastating chaos, I experienced glimmers of hope and healing.

By Meagan Cain

Since my return from Nepal in August, I’ve had a lot of people ask me how it went. It seems an easy enough question but the answer is far more complicated.

I’d been to Nepal before and had seen a side of this small Himalayan nation that tourists

often miss. I spent the summer of 2014 setting up and running basic public health

workshops for sexually-exploited women and children in Kathmandu.

That summer, I learned a lot about what people are capable of, from women who had

been sold into prostitution by their husbands, to young girls who had been gang-raped

by strangers. I witnessed horrendous human cruelty and depravity, but left Nepal inspired

by the glimmers of hope and resilience these individuals exuded. It was an experience

that left me raw and humbled and aching to do more with vulnerable women there.

It was from this yearning that “Girls Moving Mountains” emerged.

Editor's Note:

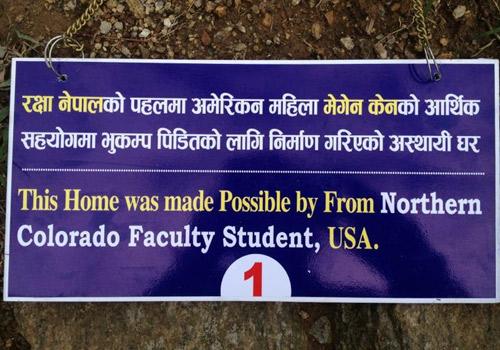

When UNC's Colorado School of Public Health graduate student Meagan Cain heard about the April 25 earthquake in Nepal, she realized that it might mean some changes in her plans for Girls Moving Mountains, her health education and human-trafficking avoidance program for young girls living in the Kumari, a rural district in the center of the country. But Cain, whose degree emphasis is community health, didn't realize just how big the changes would be, or how her three-month experience in Nepal would change her. Here is her story, in her own words.

The rural district of Kumari faces many challenges, including extreme poverty, disease,

child marriage, lack of opportunity and human trafficking. Years ago, a group of trekkers

aspired to help this somewhat hopeless situation by building the first medical clinic

in the Kumari. They called their organization “Health & Ed 4 Nepal.”

The Sukoman Memorial Polyclinic was the first attempt at introducing Western medicine

into a rural, tribal area of Nepal that had long been forgotten by its own government.

With help from the clinic staff and the unwavering support of Health & Ed 4 Nepal,

we laid the foundation for the women’s health program, and I booked my ticket into

Kathmandu for mid-May 2015. It was almost a fairytale start.

Then, on April 25, a massive, 7.9 earthquake changed everything. Media images poured

in showing collapsing buildings, frantic searches for survivors and once-beautiful

temples reduced to rubble. The organization I’d worked with had its safe house for

exploited children completely cracked and many of the women I had worked with — who

were already on the fringes of society — simply disappeared.

The shock and indescribable sadness I experienced upon hearing the news and, often

unsuccessfully, trying to contact survivors, reminded me in some ways of Sept. 11,

2001. Bad news continued to hit Health & Ed 4 Nepal like turbulent waves: the clinic

was destroyed, there weren’t enough supplies, all schools had been destroyed, aftershocks

continued to hit daily, no government help was coming, the village was completely

exposed to the elements and freezing in the rain.

Within days of mass evacuations, the U.S. Department of State issued an official

travel advisory for Nepal, urging all U.S. citizens to avoid travel there for at least

the next six months. With my departure date just weeks away, Health & Ed 4 Nepal and

I discussed canceling my proposed plans for a health program.

There were many concerns: unstable and crumbling buildings, outbreaks of cholera

and other diseases, reports of rape, and rumors of civil unrest. The biggest scare

was that a stronger quake was still to come. Given these very real concerns, it might

have been smartest to cancel my plans. However, there were still reasons to go. The

village needed health information now more than ever and Health & Ed 4 Nepal needed

a contact on the ground who could carry supplies past government seizures and report

back on the situation.

Two days before I departed to Kathmandu, the second earthquake hit. The last time

I talked to my family before boarding the plane, they told me that a U.S. military

helicopter had been found with no survivors and it would be insane to get on the plane.

With four duffel bags filled with medical supplies (marked as personal baggage to

slip by the Nepali government’s new blockade of supplies), plus a small tent and sleeping

bag, I said goodbye to everything I’d known and stepped on board.

I arrived in Kathmandu on May 15. The descent into this Himalayan nation was starkly

different than my previous trip. Tent cities littered the ground and the airport was

almost empty, except for relief aircrafts and crates of emergency supplies that filled

the tarmac.

My first obstacle was finding a place to stay in the city until I journeyed on to

the Kumari. While most buildings still stood, many individuals had fled to the crowded

IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camps. These were set up around Kathmandu because

of the uncertainty over which buildings were deemed safe and which were at risk for

collapse.

While I waited, there was a certain protocol for staying in Kathmandu that one quickly

became accustomed to. At the onset of an aftershock — which usually occurred at the

most inconvenient and unexpected of times, like in the middle of the night or upon

stepping into a shower — your first option is to throw yourself into a doorway and

hope the walls fall away from the frame. However, the best response is to bolt outside

and continue to run until you’ve found open sky, at which point you roll into the

classic fetal position. (Even after returning to Colorado, my heart still races to

my throat when a door is slammed too hard or when someone running down the hallway

causes small vibrations on the floor.)

The journey to the Kumari was its own adventure. Not long after I arrived, landslides

and monsoonal rains washed away the only road to this remote area. Mosquitoes, intense

heat, a roaming tiger, falling rocks and infections were just some of the everyday,

“average” concerns.

My first weeks in the remote outpost were lonely and quiet, occasionally interrupted

by a villager coming in for medical care. Even a month after the latest aftershock,

villagers still came in with infected wounds, broken bones or other maladies allowed

to worsen in the inhospitable environment.

There was the elderly man who had been buried under rubble for four days until he

was able to dig himself out and limp the day’s journey to the remains of the clinic;

there was the woman who had miscarried from stress when the ground first shook; there

was the young man who had severe gangrene spreading across his side because his wound

had gone untreated and infected for weeks. And there was the young pregnant girl whose

abdominal pains remained undiagnosed due to not having access to any ultrasound equipment.

Every day in the village was a lesson in humanity and accepting the things that were

beyond my abilities to help.

I struggled through landslides, constant aftershocks and a nagging doubt that maybe

Nepal would never be whole again. One evening in Kathmandu, after staying out past

dark, I was followed into an alley by two men on a motorbike. After ignoring their

repeated attempts to engage my attention, they pulled in front of my path and shut

the bike off. With only a small pocket knife held in front of me, I kept my voice

steady while yelling Chiana! (No!) as loud as I could.

It was only when I pulled out my cellphone (with its long-dead battery), and feigned

calling the police, that the two men left in search of an easier target. When I told

my Nepali friend of the incident, she laughed, telling me that a group of men had

recently accosted a landlord in the same alley and forcibly spread out his ring-laden

fingers to be cut off with their knives.

Despite the constant threats that kept my heart racing, I had little victories that

overshadowed even the worst of days. I participated in numerous relief supply distributions,

most of them led by women and girls. I traveled with a 12-year-old survivor of rape,

who had been banished from her village for voicing the crime committed against her,

to deliver the only aid to the very community that had shamed her. In Kathmandu, I

distributed supplies to street-based sex workers and their children who were being

re-victimized by the police and other agencies after the earthquakes. I helped pull

a supply-laden truck through the muck to get to a cut-off village in the Everest District.

And in the Kumari, the village youth and I got together daily at 5 a.m. to build a

community greenhouse and to have open discussions about women’s health.

It was challenging, heartbreaking, unpredictable and an incredible experience for

anyone who has ever wondered how life continues in the most despairing of situations.

When people ask me how my trip to Nepal was, I have learned to gauge my response depending

on the situation and the person. When I first returned to Colorado in August, I would

try to quickly blurt out the complexities of emotions I experienced — both good and

sometimes very bad. However, as I told my story again and again, I began to notice

that the unfortunate soul who had asked wasn’t really looking for a long-winded, emotional

novel. Answering about “Nepal” has become a lot like answering how your weekend went

— keep it short and always end on a positive. So now I have learned to answer with

a simple “Great,” and then we can move on.

A lot of people here in the United States who only watched the devastation unfold

from a TV screen or a newspaper headline have very much moved on to the next story.

And I cannot blame them. I take solace in knowing that even if my efforts were very

small drops against a large ocean of despair, I have perhaps become more human through

witnessing this struggle. Nepal taught me a lot about others, but it taught me even

more about myself. I’ve learned that my story doesn’t start, nor does it end, with

an earthquake. It was one small journey Nepal allowed me to be part of.

Update:

Shortly after she returned from Nepal, Cain received the Colorado Public Health Association’s first-ever Student Award for Excellence in Public Health Practice at the group’s annual conference in Vail. The award recognized her efforts in Nepal as well as her work with refugees in Greeley. For more photos and commentary from Cain, search Girls Moving Mountains on Facebook.